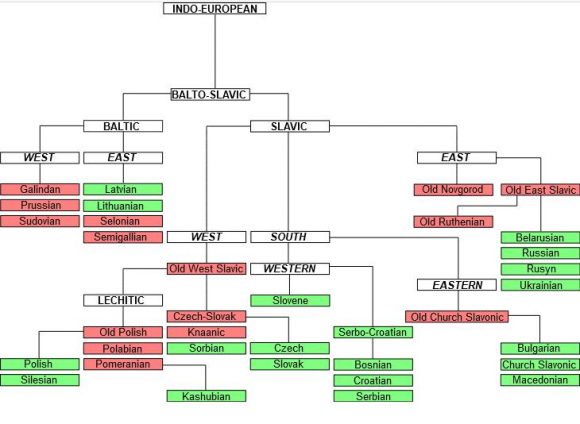

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavic peoples or their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic, spoken during the Early Middle Ages, which in turn is thought to have descended from the earlier Proto-Balto-Slavic language, linking the Slavic languages to the Baltic languages in a Balto-Slavic group within the Indo-European family.

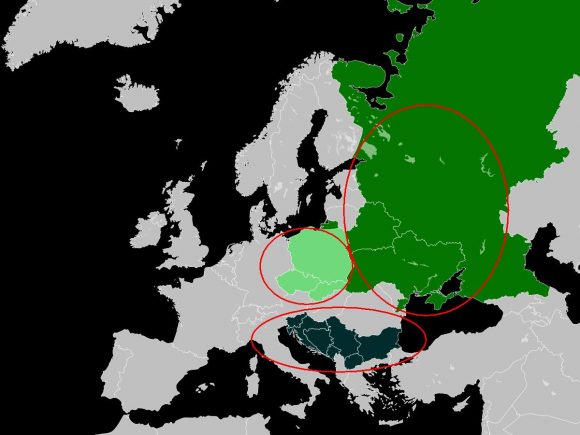

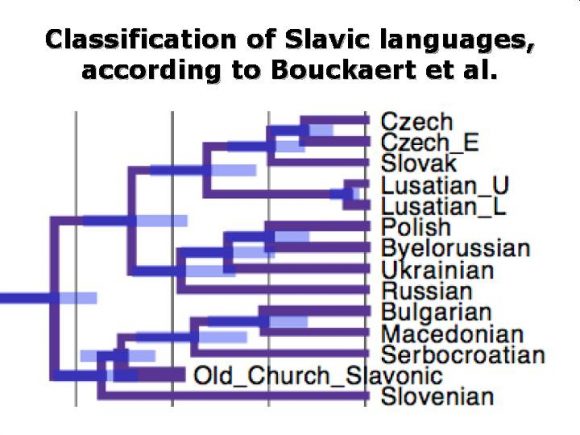

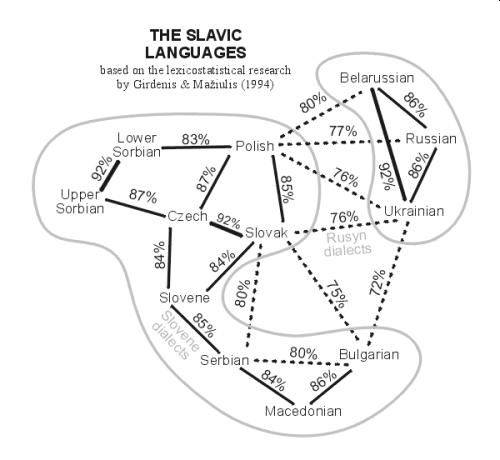

The Slavic languages are conventionally (that is, also on the basis of extralinguistic features) divided into three subgroups: East, West, and South, which together constitute more than 20 languages. Of these, 10 have at least one million speakers and official status as the national languages of the countries in which they are predominantly spoken: Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian (of the East group), Polish, Czech and Slovak (of the West group) and Bulgarian and Macedonian (eastern dialects of the South group), and Serbo-Croatian and Slovene (western dialects of the South group).

The current geographic distribution of natively spoken Slavic languages includes Southern Europe, Central Europe, the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and all of the territory of Russia, which includes northern and north-central Asia (though many minority languages of Russia are also still spoken). Furthermore, the diasporas of many Slavic peoples have established isolated minorities of speakers of their languages all over the world. The number of speakers of all Slavic languages together was estimated to be 315 million at the turn of the twenty-first century, it is the largest ethno-linguistic group in Europe.

Some linguists speculate that a North Slavic branch has existed as well. The Old Novgorod dialect may have reflected some idiosyncrasies of this group. Mutual intelligibility also plays a role in determining the West, East, and South branches. Speakers of languages within the same branch will in most cases be able to understand each other at least partially, but they are generally unable to across branches (which would be comparable to a native English speaker trying to understand any other Germanic language besides Scots).

The most obvious differences between the East, West and South Slavic branches are in the orthography of the standard languages: West Slavic languages (and Western South Slavic languages – Croatian and Slovene) are written in the Latin script, and have had more Western European influence due to their proximity and speakers being historically Roman Catholic, whereas the East Slavic and Eastern South Slavic languages are written in Cyrillic and, with Eastern Orthodox or Uniate faith, have had more Greek influence. East Slavic languages such as Russian have, however, during and after Peter the Great’s Europeanization campaign, absorbed many words of Latin, French, German, and Italian origin.

The tripartite division of the Slavic languages does not take into account the spoken dialects of each language. Of these, certain so-called transitional dialects and hybrid dialects often bridge the gaps between different languages, showing similarities that do not stand out when comparing Slavic literary (i.e. standard) languages. For example, Slovak (West Slavic) and Ukrainian (East Slavic) are bridged by the Rusyn language/dialect of Eastern Slovakia and Western Ukraine. Similarly, the Croatian Kajkavian dialect is more similar to Slovene than to the standard Croatian language.

Although the Slavic languages diverged from a common proto-language later than any other group of the Indo-European language family, enough differences exist between the various Slavic dialects and languages to make communication between speakers of different Slavic languages difficult. Within the individual Slavic languages, dialects may vary to a lesser degree, as those of Russian, or to a much greater degree, like those of Slovene.

The imposition of Old Church Slavonic on Orthodox Slavs was often at the expense of the vernacular. Says WB Lockwood, a prominent Indo-European linguist, „It (O.C.S) remained in use to modern times but was more and more influenced by the living, evolving languages, so that one distinguishes Bulgarian, Serbian, and Russian varieties. The use of such media hampered the development of the local languages for literary purposes, and when they do appear the first attempts are usually in an artificially mixed style.“

Lockwood also notes that these languages have „enriched“ themselves by drawing on Church Slavonic for the vocabulary of abstract concepts. The situation in the Catholic countries, where Latin was more important, was different. The Polish Renaissance poet Jan Kochanowski and the Croatian Baroque writers of the 16th century all wrote in their respective vernaculars (though Polish itself had drawn amply on Latin in the same way Russian would eventually draw on Church Slavonic).

14th-century Novgorodian children were literate enough to send each other letters written on birch bark.

Although Church Slavonic hampered vernacular literatures, it fostered Slavonic literary activity and abetted linguistic independence from external influences. Only the Croatian vernacular literary tradition nearly matches Church Slavonic in age. It began with the Vinodol Codex and continued through the Renaissance until the codifications of Croatian in 1830, though much of the literature between 1300 and 1500 was written in much the same mixture of the vernacular and Church Slavonic as prevailed in Russia and elsewhere.

More recent foreign influences follow the same general pattern in Slavic languages as elsewhere and are governed by the political relationships of the Slavs. In the 17th century, bourgeois Russian (delovoi jazyk) absorbed German words through direct contacts between Russians and communities of German settlers in Russia. In the era of Peter the Great, close contacts with France invited countless loan words and calques from French, many of which not only survived but also replaced older Slavonic loans. In the 19th century, Russian influenced most literary Slavic languages by one means or another.

Differentiation: The Proto-Slavic language existed until around AD 500. By the 7th century, it had broken apart into large dialectal zones.

There are no reliable hypotheses about the nature of the subsequent breakups of West and South Slavic. East Slavic is generally thought to converge to one Old East Slavic language, which existed until at least the 12th century.

Linguistic differentiation was accelerated by the dispersion of the Slavic peoples over a large territory, which in Central Europe exceeded the current extent of Slavic-speaking majorities. Written documents of the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries already display some local linguistic features. For example, the Freising manuscripts show a language that contains some phonetic and lexical elements peculiar to Slovene dialects (e.g. rhotacism, the word krilatec). The Freising manuscripts are the first Latin-script continuous text in a Slavic language.

The migration of Slavic speakers into the Balkans in the declining centuries of the Byzantine Empire expanded the area of Slavic speech, but the pre-existing writing (notably Greek) survived in this area. The arrival of the Hungarians in Pannonia in the 9th century interposed non-Slavic speakers between South and West Slavs. Frankish conquests completed the geographical separation between these two groups, also severing the connection between Slavs in Moravia and Lower Austria (Moravians) and those in present-day Styria, Carinthia, East Tyrol in Austria, and in the provinces of modern Slovenia, where the ancestors of the Slovenes settled during first colonisation.

All Slavic Languages in one video

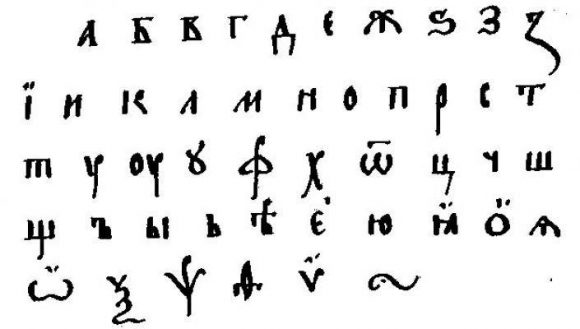

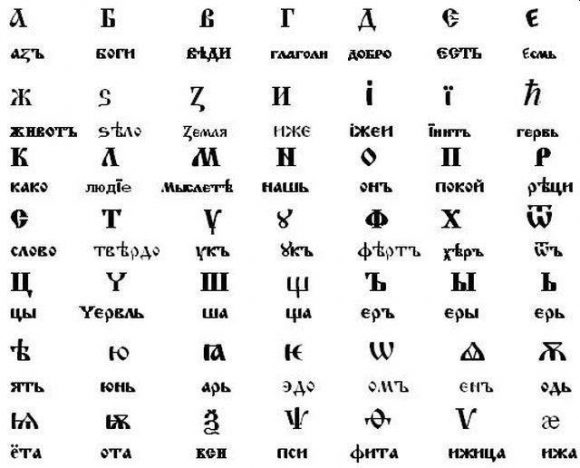

Cyrillic alphabet, writing system developed in the 9th–10th century ce for Slavic-speaking peoples of the Eastern Orthodox faith. It is currently used exclusively or as one of several alphabets for more than 50 languages, notably Belarusian, Bulgarian, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Macedonian, Montenegrin (spoken in Montenegro; also called Serbian), Russian, Serbian, Tajik (a dialect of Persian), Turkmen, Ukrainian, and Uzbek.

The first historian of ancient Slavic alphabet Bulgarian scholar, scientist-monk Chernoryzets Hrabr who lived in the X century at the court of the Bulgarian Tsar Simeon, in his book „About writing“ tells the story of two phases of the Slavonic writing.

The first stage was when the Slavs were still pagans, so use dashes and serifs.

The second stage was after the adoption of Christianity, when they began to write Roman and Greek inscriptions.

And it was so, until the great enlighteners of the Slavs – brothers Cyril and Methodius were created an alphabet.

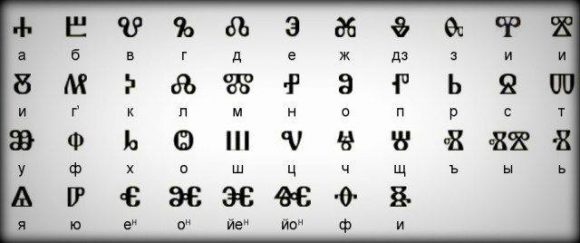

Glagolitic is the ancient system of Slavic writing, signed by Saint Cyril, in order to translate Greek religious text to Slavic.

It is on the basis of this alphabet that the Cyrillic alphabet was developed in the First Bulgarian Empire during the 10th century AD by the followers of the brothers, who were beatified as saints.

Cyrillic is an advanced writing system, named after St. Cyril (or Constantine).

Their disciples constructed a new script for Slavic, based on capital Greek letters, with some additions; confusingly, this later script (drawing on the name of Cyril) became known as Cyrillic. Saints Naum and Clement, both of Ohrid and both among the disciples of Cyril and Methodius, are credited with having devised the Cyrillic alphabet.

That Cyrillic Bulgarian alphabet was used for hundreds of years and has become the foundation of modern alphabets of many Slavic nations.

.

.