The effects of technology on job creation/destruction by skill level

Scott Santens

„47 Percent…“

.

That’s the highly cited estimate out of Oxford by Frey and Osbourne of the percentage of existing jobs that are likely to be automated away with the help of technology within the next two decades. According to this paper, flip a coin and call heads or machines to see if your job will exist in 20 years. This is the 21st century fear for many called „technological unemployment.“

There is also a conception among many (about half of those considered experts, so again flip a coin) that there is no technological unemployment problem because even though technology eliminates jobs, it also creates new and better ones of sufficient supply such that pretty much everyone is better off than they would be in otherwise „undisrupted“ lives.

There does tend to be one caveat to this dismissal of automation fears that most of all of these high-skill jobs will require high-skill labor, and thus a highly skilled work force which will require more education. So of course the answer to what could otherwise be a somewhat thorny future, is simply education, education, and more education.

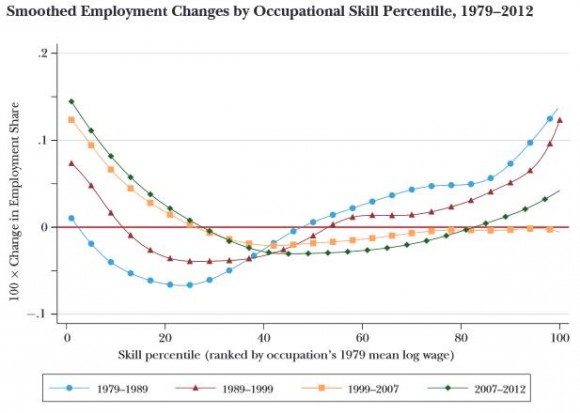

Well, David Autor of MIT just published a fascinating paper (though we reach different conclusions) in the Summer 2015 Journal of Economic Perspectives titled, „Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation“. In this paper he compiled the following chart, and it should blow anyone’s mind who holds a strong opinion about the historical effects on jobs of computing technology since it took off in the 1970s, and so the possible future we should expect if the trends continue.

This chart has some very interesting complexity to it, which I’ll attempt to simplify with snippets from Autor’s paper. The most important thing to recognize is that all points above the flat red line show relative growth in jobs while points below show relative loss in jobs. Points to the left show jobs with less skill required and points to the right show jobs with more skill required. Each curve represents basically a different decade.

Three Important Employment Observations

First, the pace of employment gains in low-wage, manual task-intensive jobs has risen successively across periods, as shown at the left-hand side of the figure.

If we look at the far left of the chart, we see growth in jobs with the least skill, increasing decade after decade after decade. As the story goes, technology should have the opposite effect. The simpler a job is, the easier it should be to automate, and yet we’re not seeing this at all. Instead we’re seeing more and more low-skill jobs being created not destroyed.

Second, the occupations that are losing employment share appear to be increasingly drawn from higher ranks of the occupational distribution. For example, the highest ranked occupation to lose employment share during the 1980s lay at approximately the 45th percentile of the skill distribution. In the final two subperiods, this rank rose still further to above the 75th percentile—suggesting that the locus of displaced middle-skill employment is moving into higher-skilled territories.

Where these curves intersect the red line has been moving to the right, meaning that more and more middle-skill jobs have been lost in a way that even increasingly eats into higher and higher skill ranges. This is a hollowing out of the middle and even upper-middle. Jobs that require what’s considered between a low and high amount of skill have been disappearing. This appears to reflect the loss of the middle class. As each decade passes, the jobs that require mostly a medium amount of skill are simply going away, replaced instead with jobs requiring less skill ,not more skill, and thus jobs that tend to pay less, not more.

Third, growth of high-skill, high-wage occupations (those associated with abstract work) decelerated markedly in the 2000s, with no relative growth in the top two deciles of the occupational skill distribution during 1999 through 2007, and only a modest recovery between 2007 and 2012. Stated plainly, the growth of occupational employment across skill levels looks U-shaped earlier in the period, with gains at low-skill and high-skill levels. By the 2000s, the pattern of occupational employment across skill levels began to resemble a downward ramp.

We should expect to see what we see on the left of this chart on the right instead, but we don’t. Between 1979 and 2007, a span of almost 30 years, there was less and less growth in jobs requiring the most skill. Only since 2007 has there been a reversal with a small amount of growth in these jobs. Other than that, as Autor himself describes it, it looks like a „downward ramp“, meaning that both middle and high-skill jobs are being steeply replaced with low-skill jobs, and have been since the 1970s.

This is not the story we are told. Instead we read story after story like this latest one from the Guardian, claiming that 140 years of job creation show that jobs will always be created. And yet the ongoing trend of such articles is to mostly ignore the potentially unnecessary nature of the jobs themselves, the level of skill involved to perform them, and the lower pay they can command than the jobs they are replacing. Take for example the following excerpt:

Their conclusion is unremittingly cheerful: rather than destroying jobs, technology has been a “great job-creating machine”. Findings by Deloitte such as a fourfold rise in bar staff since the 1950s or a surge in the number of hairdressers this century suggest to the authors that technology has increased spending power, therefore creating new demand and new jobs.

So there’s no need to worry about technological unemployment, because there will always be a need for more bar-backs and haircuts? Is that bar-back better off no longer having a manufacturing job paying $40,000 per year and instead having a job paying $20,000 per year in the service industry? Is that an important job to the human species, bringing empty glasses from Point A to Point B? And is this a job that just can’t possibly be done by a machine, or outright eliminated? Ever? Is the service industry really safe?

We should also probably keep in mind that the percentage of the population in the labor force peaked back in the year 2000, and has been falling since. The above chart of employment skills polarization only examines the makeup of those employed, and ignores all those unemployed and all those not even looking for work anymore. The amount of those employed within the total population is at a record 38-year low of 62.6%. Meanwhile, despite slowing, GDP is still growing, so all the work is still obviously getting done somehow…

Many Questions Unasked

Centuries of data may show us how jobs have been both destroyed and created but recent decades worth of more nuanced data more importantly show us there’s more to this story. Whenever we see someone claiming new jobs are being created and will continue to be created so as to provide everyone a job, we need to look deeper and ask, „What kind of job? What are the skills required? How much does it pay for how many hours? Does it provide more security or less? What are the benefits it offers? Is the job really necessary? Does the job provide meaning to those tasked with it? Are jobs and work the same thing? Is there work to do that’s more important than what the job involves? Is working in the job actually better than not working at all?„

Regarding that last question in particular, there’s this important finding which should not go ignored in any discussion celebrating job creation:

Those who moved into optimal jobs showed significant improvement in mental health compared to those who remained unemployed. Those respondents who moved into poor-quality jobs showed a significant worsening in their mental health compared to those who remained unemployed.

That’s right, having no job at all can be better than having a bullshit one. Thanks, science. And if low-skill jobs are more likely to be worse on mental health than medium and high-skill jobs, then for decades we’ve been increasingly working in newly created jobs that are depressingly worse for us than not working in any job.

All of the above questions are important to actually ask because when we get right down to it, the mere existence of a job means very little. We have to ask additional questions about the nature of the job itself. Those not asking these additional questions are simplifying the story in such a way it becomes even simpler than a story. It becomes a fairy tale.

Yes, our economy is so far creating more and more jobs as our technology destroys old ones, but these jobs are not at all the jobs we may assume they are. They are mostly low-skill jobs, and that means mostly low-paying jobs. For every new job as a Facebook engineer, there are countless more jobs in fast food, and there are a whole lot fewer jobs in car assembly plants. There are also not as many total jobs available for everyone as we may think. What does this all mean to us and to our country as a whole? What does it mean for the great increases in productivity we could otherwise see if job elimination were instead actually our goal?

This also means that more education isn’t the answer. As the decades have passed, the population has gotten more and more educated. Our workforce now is the most educated workforce in US history, and a great deal of this education is being put to work in jobs that don’t need it, because the jobs that do need it aren’t being created in sufficient numbers. Are bar-backs with PhDs a triumph of new job creation?

The true story of technology and jobs is a story of an eroding middle, a relatively slowing top, and a vastly growing bottom.

So unless we all wish to pursue insecure lives of low-skill underpaid mostly meaningless employment thanks to all the machines increasingly doing all the rest of the work (not really for us but mostly for the benefit of those who own them), we will need to break the connection between work and income by providing everyone an income floor sufficient to both meet basic needs and purchase the goods and services the machines are providing. It’s as simple as that. Without that decoupling, there will be no economy, because there will be insufficient consumer buying power to drive it.

If we look at the details of the last few decades of job creation and destruction, we’re either going to make enough new low-skill jobs in numbers sufficient to keep unemployment numbers low enough to actually run a society… or we’re not. Either way, consumer buying power is likely to steeply erode, even after we account for the effects technology has on lowering prices because the costs of basic needs like food and housing are the costs technology has had relatively little effect on this century. Meanwhile, if we can eliminate half of our jobs in just 20 years, do we really even want to create that many tens of millions of new ways to work for someone else? Why?

There appears to be no happy ending to this story that doesn’t involve universal basic income. So instead of continuing to ask if jobs are going to be automated in sufficient quantities to need basic income, let’s instead start to increasingly ask if there’s any job we can’t automate so we’re all more freed to live by it.