Bulgarians have terms for every relative imaginable. Get to know your svekarva, tashta, lelya, svako, chicho, strinka, vuyna, vuycho, baldaza, dever, badzhanatsi, etarvi and zalvi. Don’t forget your shurey.

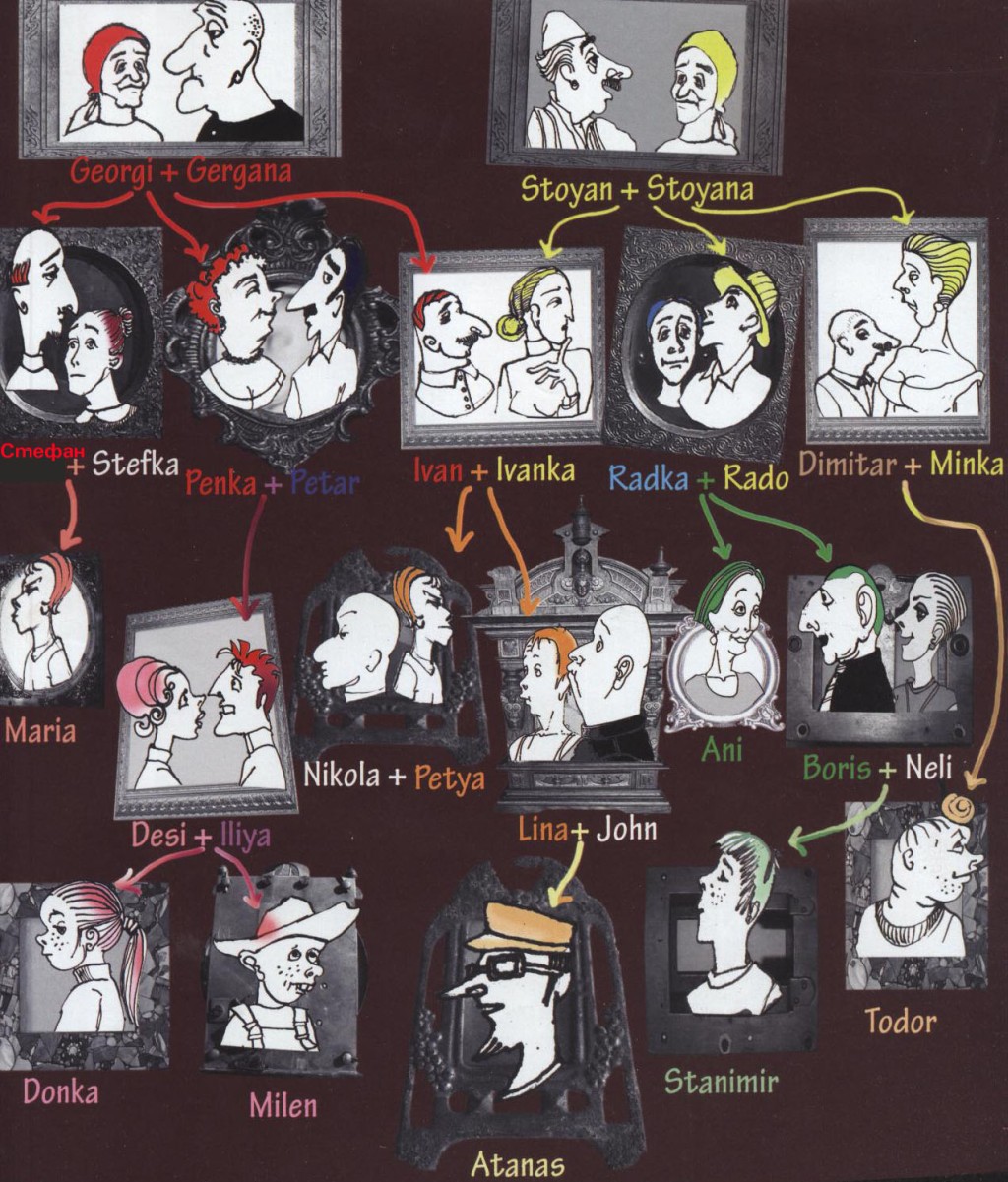

by Dimana Trankova; illustration by Gergana Shkodrova

Ask any Bulgarian what was their recent family gathering like and the answer will probably sound something like this: “A disaster. My badzhanak got into an argument with my tashta, my strinka showed up with her annoying vuyna, then my shurey got completely tanked and my sister was really upset. Thank God our third cousins from Pavlikeni weren’t able to make it!”

Sound like a nightmare? The truth is even scarier: all those monstrously unpronounceable words refer to your friend’s relatives. The above is in fact only a small sampling of all the baffling kinship terms that exist in Bulgarian. You’re probably able to describe your relationships to extended family members with a modest vocabulary that includes grandfather, grandmother, father-in-law, mother-in-law, brother-in-law, sister-in-law, son-in-law, daughter-in-law, uncle, aunt, nephew, niece and cousin. Having this small set of familial terms to work with would immediately throw Bulgarians into simultaneous identity and existential crises. While most of them don’t know their paternal great-great-grandfather’s name, they all know how to differentiate between paternal and maternal uncles, as well as the proper terms for their wives, which is far more complicated than a simple “auntie”.

Start your exploration of the Bulgarian family tree with the straightforward term lelya, used to refer to your mother or father’s sister. Her husband’s title, however, is not simply uncle, but either svako, lelincho or kaleko, depending on the region of Bulgaria you are in. When it comes to your mother or father’s brothers, the situation gets much more complicated. Chicho can be used only for a paternal uncle. But don’t make the mistake of calling his wife lelya; she’s your strinka or chinka. Things are completely different for your mother’s brother. He is vuycho to you, and his wife is your vuyna or uchinayka.

Think things couldn’t get any more confusing? Think again – the fun is just beginning. Truly complex familial relationships – and not just in terms of kinship – start with the wedding. The union of two large families gives rise to yet more bewildering terminology.The most important terms refer to the newlyweds’ parents.

When a young couple decides to marry, their parents become each other’s svatove, or in-laws. For centuries Bulgarian in-laws called each other by this title; recently, however, this custom has begun to disappear. Nevertheless, an elderly woman might still call up her son and ask after the health of his mother-in-law with the query: “How is my svatya?”

In Bulgarian the terms “zet” and “snaha” are the exact equivalents of the English son-in-law and daughter-in-law; however, mother-in-law and father-in-law are not so simple. To a Bulgarian wife, her husband’s father and mother are her svekar and svekarva, but when speaking to them she calls them tatko and mayko, or dad and mum. Her husband, on the other hand, thinks of her parents as his tast and tashta, and addresses them with the “affectionate” titles of dyado and babo, or grandpa and grandma.

This may seem a little unfair; after all, the bride’s parents aren’t necessarily doddering old geezers. The tradition is a remnant of rural Bulgarian society. Prior to industrialisation at the turn of the 20th Century, most Bulgarians lived in villages. So they needed a complex kinship system to regulate relationships within large families living close together.

Newlyweds typically moved into the groom’s home, where his parents, the svekar and svekarva, ruled the household. For them the bride was something like a new daughter – one expected to be even more obedient than their own children. The fact that she had to call them mum and dad was only the tip of the hierarchical iceberg. To show respect for her new “parents,” the daughter-in-law would govee, or remain completely silent in their presence, for the first few months of her marriage.

The difficult life of a young bride living under one roof with her mother-in-law was immortalised in numerous Bulgarian folksongs and is still a sore subject for these village women’s great-great granddaughters today. Ask any Bulgarian woman and she’ll be happy to launch into a string of horror stories about living with her mother-in-law, usually topped off by a snide joke on the topic. For example, have you seen that picture of Asclepius’ snake outside the chemist’s? The model for it was “my mother-in-law at a cocktail party”.

Which isn’t to say that the relationship between a young husband and his mother-in-law is all wine and roses – especially if for some reason the newlyweds have to move in with the bride’s parents. In that case, the poor guy is labelled a zavryan zet, imaginatively translated as “husband under the carpet,” and finds himself the butt of many tired family jokes. In one such tale, the beleaguered chap has to sleep between the window and a potted fern – so that the draught won’t damage the plant. In other cases, however, the tashta cherishes his daughter’s husband even more than his own children, hence the saying: Zet kato med, sin kato pelin, or a son-in-law like honey, and a son like wormwood wine.

All these svekarvi and tashti are only the beginning of a complicated familial hierarchy that also includes all the newlyweds’ brothers and sisters. The husband should call his wife’s brother shurey, while the latter’s spouse is his shurenayka or shurolinka. A man calls his wife’s sister his baldaza, a Turkish word meaning “little or back-up wife”. When two sisters get married – to different men, that is – their husbands become badzhanatsi to each other. The names for the husband’s siblings are equally complex. A woman calls her husband’s sister zalva and his brother dever, while the wives of two brothers are etarvi.

Confused? Sometimes the Bulgarians themselves get mixed up. With uncharacteristic self-mockery, they have come up with a saying that pokes fun at this cacophony of family terminology. Na baba Zlata shureya, or Grannie Zlata’s shurey is a humorous idiom – remember that a woman cannot have a shurey. The phrase can express suspicion at an unsubstantiated rumour: “I think you must’ve heard that from your Grannie Zlata’s shurey.” You can also use it to voice indignation: “How dare you speak to me like that! Who do you think I am, your Grannie Zlata’s shurey?”

If the phrase is just said on its own, however, it unequivocally expresses one thing: frustration. So why did Bulgarians decide to complicate their lives with all these strinki, baldazi and deveri in the first place? One possible answer is 500 years of Ottoman rule. After the Ottoman Turks conquered Bulgarian lands at the end of the 14th Century, they deliberately suppressed all forms of local leadership. The medieval aristocracy was killed off during wars and subsequent revolts, or else sent into exile to Anatolia, where it was absorbed in the general population. The religious establishment was also destroyed when the independent Bulgarian Church fell under the control of the Greek Patriarchate.

This left the common people with little political representation within the empire. For the next five centuries of Ottoman rule, the family was the primary unit of organisation in rural Bulgarian society. During this time families were quite large and usually lived together under one roof. To make up for the lack of an external hierarchy and to establish a pecking order within this tightly-knit community, Bulgarians came up with terms to describe every possible type of familial relationship. This also made it easier to remember who fits where in the family tree; it’s much simpler to say “Penka is Maria’s etarva” instead of “Penka is married to Ivan, who is the brother of Maria’s husband Peter”.

After Bulgaria’s independence from the Ottoman Empire in the late 19th Century and its subsequent industrialisation, these old familial structures gradually began to break down. The perplexing system of kinship terms has nevertheless survived as a relic of the times when extended families lived together.

Recent generations have begun to forget this dated terminology; however, frequent family reunions on major holidays still serve to remind young Bulgarians of the meaning – and usefulness – of words like zalva. But what about nephews and cousins? Fortunately they are simply plemenitsi and bratovchedi, no matter whether they’re from mum or dad’s side of the family. The only distinction made is between generations.

Figuring out the family

Feel like you need to be Einstein’s second cousin to keep all this straight? Don’t worry; you can always rely on our handy kinship dictionary and family tree

LELYA – your mother or father’s sister. For example, Ivanka is lelya to Ani, Boris and Todor, just as Penka is lelya to Maria

SVAKO, LELINCHO, KALEKO – your lelya’s husband. Ivan is svako to Ani, Boris and Todor, just as Petar is to Maria

CHICHO – your father’s brother; his wife is your STRINKA or CHINKA. Ivan is Petya’s chicho, and Ivanka is her strinka

VUYCHO – your mother’s brother; his wife is your VUYNA or UCHINAYKA. Ivan is vuycho to Iliya, and Ivanka is his vuyna. The same goes for Rado and Radka, who are vuycho and vuyna to Petya, Mina and Todor

TAST and TASHTA – your wife’s parents. Stoyan and Stoyana are Ivan’s tast and tashta, whom he calls dyado and babo, or grandpa and grandma

SVEKAR and SVEKARVA – your husband’s parents. Georgi and Gergana are Ivanka’s svekar and svekarva; she should call them tatko and mamo, but in reality she probably calls her mother-in-law “the old bag” or “the snake”The tast, tashta, svekar and svekarva are all SVATOVE, or in-laws, to each other

BALDAZA – a man’s term for his wife’s sister or his “back-up bride”. Minka is Ivan’s baldaza, while he is her zet

DEVER – a woman’s term for her husband’s brother. Stefan is Ivanka’s dever

BADZHANATSI – the husbands of two sisters. Dimitar and Ivan are badzhanatsi

ETARVI – the wives of two brothers. Ivanka and Stefka are etarviZALVA – a woman’s term for her husband’s sister. Penka is Ivanka’s zalva, while Ivanka is Penka’s snaha

SHUREY – a man’s term for his wife’s brother. Rado is Ivan’s shurey, and his wife Radka is his SHURENAYKA

The word “FAMILY” plays a vital role in every human life because family comes as a top priority; we are well aware of that. Like a tree has its root, stem, branches, leaf, flowers, the same as the family tree has its structure like grandparents, parents, child, and it keeps continuing from generation to generation. “Family tree,” yeah, just two simple words, but these two words are highly important for everyone’s life.

family tree or family three

.